Docs Tag: blood

Crohn’s and Colitis

WHAT ARE CROHN’S AND COLITIS?

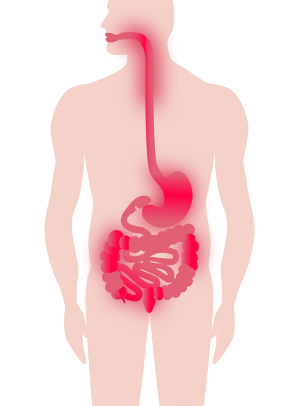

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) describes a group of conditions, the two main forms of which are Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. IBD also includes indeterminate colitis.

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are diseases that inflame the lining of the GI (gastrointestinal) tract and disrupt your body’s ability to digest food, absorb nutrition, and eliminate waste in a healthy manner.

Below you fill find more information about the anatomy and function of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

Dr. Mike Evans is founder of the Health Design Lab at the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, an Associate Professor of Family Medicine and Public Health at the University of Toronto, and a staff physician at St. Michael’s Hospital. This video was made possible through the Gastrointestinal Society, with the support of Crohn’s and Colitis Canada.

ANATOMY AND FUNCTION OF THE GI TRACT

In order to understand Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, it is first helpful to understand the anatomy and function of the healthy gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Below is a medical illustration of the GI tract. When you eat, food travels through the GI tract in the following order:

Mouth [ 1 ]

Esophagus [ 2 ] (tube that connects the mouth to the stomach)

Stomach [ 3 ] (food is mixed with stomach acid and enzymes to break down the material into smaller pieces called chyme)

Small Bowel [ 4 ] (or the ‘Small Intestine’) is made up of three sections: Duodenum [ 7 ] (about 8 cm in length); Jejunum [ 8 ] (around 3 metres long); and Ileum [ 9 ] (about 3 metres in length).

The functions of the small bowel are to digest your food and absorb the nutrients. In particular, the jejunum and ileum are the organs responsible for absorbing nutrients from your food. Without the small bowel, we would not be able to convert food into useable nutrition.

Ileocecal Valve [ 5 ] (regulates the amount of material passed from the small bowel to the large bowel and prevents “dumping” all at once)

Large Bowel [ 6 ] (also called the Large Intestine or the Colon). The colon is much wider in diameter than the small bowel and is approximately 1.5 metres long. The different sections of the colon are identified as the:

- Cecum [ 10 ] and appendix [ 11 ]

- Ascending colon

- Hepatic flexure (a bend in the gut at close to the location of the liver)

- Transverse colon

- Splenic flexure (another bend located near the spleen)

- Descending colon

- Sigmoid colon

- Rectum [ 12 ]

- Anus [ 13 ]

The main functions of the colon are to extract water and salt from stool, and store it until it can be expelled via the anus.

Bowel movements are an entirely different matter for someone with Crohn’s or colitis. Individuals with these diseases face some very real challenges related to feelings of urgency, diarrhea, and bloody stool.

WHAT IS CROHN’S DISEASE

Crohn’s disease is named after the doctor who first described it in 1932 (also known as ‘Crohn disease’).

Inflammation from Crohn’s can strike anywhere in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, from mouth to anus, but is usually located in the lower part of the small bowel and the upper colon.

Patches of inflammation are interspersed between healthy portions of the gut, and can penetrate the intestinal layers from inner to outer lining.

Crohn’s can also affect the mesentery, which is the network of tissue that holds the small bowel to the abdomen and contains the main intestinal blood vessels and lymph glands.

WHAT IS ULCERATIVE COLITIS

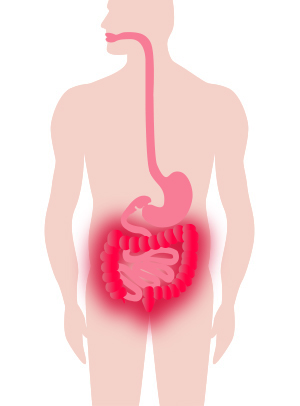

Ulcerative colitis is more localized in nature than Crohn’s disease. Typically, the disease affects the colon (large intestine) including the rectum and anus, and only invades (inflames) the inner lining of bowel tissue.

It almost always starts at the rectum, extending upwards in a continuous manner through the colon. Colitis can be controlled with medication and in severe cases can even be treated through the surgical removal of the entire large intestine.

WHAT IS INDETERMINATE COLITIS:

Indeterminate colitis is a term used when it is unclear if the inflammation is due to Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis.

SYMPTOMS OF CROHN’S DISEASE AND ULCERATIVE COLITIS

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are (lifelong) diseases. People with these diseases experience acute periods of active symptoms (active disease or flare), and other times when their symptoms are absent (remission).

Symptoms can include abdominal pain and cramping; severe diarreha; rectal bleeding; blood in stool; weight loss and diminished appetite.

Visit our Signs and Symptoms page for more information.

COMPARING CROHN’S DISEASE AND ULCERATIVE COLITIS

There are similarities and differences between Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. We’ve already described above how Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis involve different areas of the gastrointestinal tract.

Other characteristics of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis that may differ include: symptoms; the effect of surgery; treatment options; complications or extra-intestinal manifestations; and impact of smoking.

These characteristics are summarized in the table below:

| Crohn’s Disease | Ulcerative Colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Occurrence | More females than males All ages, peak onset 15-35 years |

Similar for females and males All ages, usual onset 15-45 years |

| Symptoms | Diarrhea, fever, sores in the mouth and around the anus, abdominal pain and cramps, anemia, fatigue, loss of appetite, weight loss | Bloody diarrhea, mild fever, abdominal pain and cramps, anemia, fatigue, loss of appetite, weight loss |

| Terminal ileum involvement | Common | Never |

| Colon involvement | Common | Always |

| Rectum involvement | Common | Always |

| Peri-anal disease | Common | Never |

| Distribution of disease | Patchy areas of inflammation | Continuous areas of inflammation but can be patchy once treated |

| Endoscopic findings | Deep and snake-like ulcers | Diffuse ulceration |

| Depth of inflammation | May be transmural, extending through the entire thickness of the wall of an organ or cavity deep into tissues | Shallow, mucosal |

| Fistulas between organs | Common | Never |

| Stenosis | Common | Never |

| Granulomas on biopsy | Common | Never |

| Effect of surgery | Often return following removal of affected parts. Decreased likelihood of pregnancy. | Usually cured by removal of colon (colectomy). Decreased likelihood of pregnancy after ileoanal pouch. |

| Treatment options | Drug treatment (corticosteroids, immune modifiers, biologic therapies). Exclusive formula diet in children. Surgery (repair fistulas, remove obstruction, resection, and anastomosis). | Drug treatment (5-aminosalicylates, sulfasalazine, corticosteroids, immune modifiers, biologic therapies). Surgery (rectum/colon removal) with creation of an internal pouch (ileoanal pouch). |

| Cure | No existing cures. Maintenance therapy is used to reduce the chance of relapse. | Through colectomy only. Maintenance therapy is used to reduce the chance of relapse. |

| Bowel complications | Blockage of intestine due to swelling or formation of scar tissue. Abscesses, sores, or fistulas. Malnutrition. Colon cancer. | Bleeding from ulcerations. Perforation (rupture) of the bowel. Malnutrition. Colon cancer. |

| Extra-intestinal disease | Osteoporosis. Liver inflammation (primary sclerosing cholangitis). Blood clots. Pain and swelling in the joints (arthritis). Growth failure (in children). Mental Illness. | Liver inflammation (primary sclerosing cholangitis). Blood clots. Eye inflammation (iritis). Pain and swelling in the joints (arthritis). Mental illness. |

| Smoking | Higher risk of acquiring for smokers | Higher risk of acquiring for ex-smokers |

| Mortality risk | Increased risk of colorectal cancer and overall mortality. Increased risk of lymphoma and skin cancer (due to treatments). | Increased risk of colorectal cancer. Uncertain change in mortality risk. Increased risk of lymphoma and skin cancer (due to treatments). |

Image reference. Impact of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Canada. 2018.

Information taken from https://crohnsandcolitis.ca/About-Crohn-s-Colitis/What-are-Crohns-and-Colitis

Bone Marrow/Stem Cell Transplant

What is the Difference Between a Bone Marrow Transplant and a Stem-cell Transplant?

There are two different types of transplants: bone marrow transplants and peripheral blood stem-cell transplants (PBSCTs). The difference between the two depends on where the stem cells are taken from. In bone marrow transplants, the stem cells are taken from the bone marrow. In PBSCTs, the stem cells are taken from the circulating blood. PBSCTs are now more commonly performed than bone marrow transplants, as the procedure is easier and the body is able to regenerate new stem cells faster.

Transplants fall into three basic donor categories:

A syngeneic transplant is when the cells are donated by an identical twin. Allogeneic is when the donor’s basic cell is almost identical to the patient’s as with a close relative (brother or sister). Rarely is the basic cell type matched by an unrelated relative.

Autologous is when the patient’s own stem cells are removed from his or her bone marrow or bloodstream. With types of NHL that have spread to the bloodstream or bone marrow, it may be difficult to obtain uncontaminated cells or cells that can be used, even after treating them in a laboratory to remove or kill the NHL cells.

Marrow or cell transplantation is done to replace healthy cells that have been destroyed by cancer treatment. Bone marrow or stem cells that have been removed from a donor are carefully frozen and stored while the patient receives high-dose chemotherapy and sometimes whole-body radiation treatment. This process kills all or most normal stem and bone marrow, while destroying cancer cells. This leaves them defenseless against infection and unable to form blood. After therapy, the frozen marrow or cells are thawed and put back in the body. During the recovery period, all of the body’s systems must be carefully monitored for rejection, infection and the need for any supportive treatments.

Information taken from https://www.lymphoma.ca/lymphoma/patient-journey/treatment/bone-marrow-transplant

Valvular Heart Disease

What is valvular heart disease?

The heart has four chambers. The two upper chambers are called the left and right atrium, and the two lower chambers are called the left and right ventricle. The four valves at the exit of each chamber maintain one-way continuous flow of blood through the heart to the lungs and the rest of the body.

The four valves are the tricuspid valve, pulmonary valve, mitral valve and aortic valve.

- Oxygen-poor blood coming into your heart from your body flows into the right atrium. The tricuspid valve is the valve between the right atrium and the right ventricle. It opens so blood can be pumped to the right ventricle.

- The pulmonary valve controls blood flow between the right ventricle and the lungs. It opens to let the heart pumps blood out of the ventricles into the pulmonary artery toward the lungs so it can pick up oxygen. The oxygen-rich blood flows back from the lungs into the left atrium.

- The mitral valve lies between the left atrium and the left ventricle. It opens so the oxygen-rich blood from the left atrium can be pumped into the left ventricle.

- The aortic valve controls blood flow from the left ventricle into the aorta (the main artery in your body). When this valve opens, the oxygen-rich blood is pumped to the aorta and then out to fuel the rest of your body.

In between each step, the valve closes to prevent blood from flowing backwards and mixing oxygen-poor blood with oxygen-rich blood. The one-way continuous flow of blood delivers oxygen throughout your body.

Heart valve disease occurs when one or more of the heart valves do not open or close properly. When it affects more than one heart valve, it is called multiple valvular heart disease.

- Stenosis is when the valve opening becomes narrow and restricts blood flow.

- Prolapse is when a valve slips out of place or the valve flaps (leaflets) do not close properly.

- Regurgitation is when blood leaks backward through a valve, sometimes due to prolapse.

Heart valve disease can be classified as mild, moderate or severe. It can lead to an enlarged heart or heart failure. Heart failure is a serious medical condition where the heart cannot pump enough blood to meet the body’s need for oxygen.

Many valvular heart diseases can be treated with medication, or surgery and other procedures to repair or replace the valve.

The four valves are the tricuspid valve, pulmonary valve, mitral valve and aortic valve.

- Oxygen-poor blood coming into your heart from your body flows into the right atrium. The tricuspid valve is the valve between the right atrium and the right ventricle. It opens so blood can be pumped to the right ventricle.

- The pulmonary valve controls blood flow between the right ventricle and the lungs. It opens to let the heart pumps blood out of the ventricles into the pulmonary artery toward the lungs so it can pick up oxygen. The oxygen-rich blood flows back from the lungs into the left atrium.

- The mitral valve lies between the left atrium and the left ventricle. It opens so the oxygen-rich blood from the left atrium can be pumped into the left ventricle.

- The aortic valve controls blood flow from the left ventricle into the aorta (the main artery in your body). When this valve opens, the oxygen-rich blood is pumped to the aorta and then out to fuel the rest of your body.

In between each step, the valve closes to prevent blood from flowing backwards and mixing oxygen-poor blood with oxygen-rich blood. The one-way continuous flow of blood delivers oxygen throughout your body.

Heart valve disease occurs when one or more of the heart valves do not open or close properly. When it affects more than one heart valve, it is called multiple valvular heart disease.

- Stenosis is when the valve opening becomes narrow and restricts blood flow.

- Prolapse is when a valve slips out of place or the valve flaps (leaflets) do not close properly.

- Regurgitation is when blood leaks backward through a valve, sometimes due to prolapse.

Heart valve disease can be classified as mild, moderate or severe. It can lead to an enlarged heart or heart failure. Heart failure is a serious medical condition where the heart cannot pump enough blood to meet the body’s need for oxygen.

Many valvular heart diseases can be treated with medication, or surgery and other procedures to repair or replace the valve.

Information taken from https://www.heartandstroke.ca/heart/conditions/valvular-heart-disease

Blood Pressure Test

What is a Blood Pressure test?

Throughout your body, your heart pumps blood through blood vessels. The heart can pump the blood fast and slow. For example, think about a garden hose. If the water is just trickling out, the water is moving slow and at a low force, but if you turn on the hose all the way, the water shoots out really fast and at a high force. This is how your blood vessels work; your heart can pump blood through the vessels slow or fast. To measure how your blood is moving around your body, the blood pressure test is used.

A blood pressure test (sphygmomanometer) measures the force (how fast or slow) of the blood moving through your blood vessels. You may remember hearing numbers when nurses and doctors are talking about your blood pressure. For example you may hear 120 over 80. The first number 120 means how fast your blood is being pushed out of your heart and into the blood vessels, this is called systolic. The other number 80 means this is how fast your blood is going back to your heart, this is called diastolic. A blood pressure test measures both how fast your blood is being pushed out of your heart and how fast your blood is going back to your heart.

Why do I need to have a Blood Pressure test?

Usually when you are in the hospital, your blood pressure is checked everyday, sometimes it can even be checked a few times a day. This just lets the doctor and nurse know how your blood is moving around your body.

What does a Blood Pressure machine look like?

The blood pressure machine has a small computer and a blood pressure cuff. The cuff is made of material with some Velcro on it. The cuff is attached to the computer by a rubber cord. It is on a cart or a small pole so that the nurses can move it around from room to room, or sometimes it is attached to the wall in your room. No picture is taken, just the numbers show up on the small computer screen for the nurses to write down and tell the doctor.

Sometimes the nurse will use a blood pressure cuff that is not attached to a computer. When the nurse uses this type of blood pressure cuff, they use a pump to pump air into the cuff to fill it with air and read the numbers from the side of the cuff where the pump is.

What happens when I have a Blood Pressure test?

A nurse will come to you with the blood pressure machine. She may ask you to roll up your sleeve. She will then place the cuff around your arm, just above your elbow. Sometimes the nurses may put the cuff on part of your leg. The nurse will then attach the Velcro to make sure it says in place. A button will then be pushed on the machine, and the cuff will start to fill with air. If the blood pressure cuff is not one that connects to a computer, then the nurse will use a pump on the side of the cuff to help the cuff fill with air. Once it has filled, you will notice that the cuff is very puffy and gives your arm a tight hug/squeeze. The machine will beep that it is done and the nurse will remove the cuff from your arm.

What will the Blood Pressure test feel like?

The nurse will wrap a small cuff around a part of your arm or your leg. When the machine is on, the cuff fills with air. The cuff will get snug (tight) around your arm or leg. Do not worry, the cuff will stop filling with air when it is done, and the air will be let out of the cuff. It is important to relax and stay still so that the test will be short. If you move your arm or leg around, the test will take longer which means the snug cuff will be on your arm or leg longer. The test should take less then a few minutes and will be done a few times a day, sometimes even at night. Sometimes it can help to think of something else, like your favourite place or song, while having the blood pressure done. Other ideas to try to help you lie still are quiet activities like blowing bubbles or watching your favourite movie.

Preparing for the test

There is nothing that you need to do to prepare for a blood pressure test. You do not have to go anywhere to have the test done; your nurse will come into your room with the machine and check it for you.

Remember

If you have any questions about the test, always ask!

Congenital Heart Defects

What is congenital heart disease?

Congenital heart disease is a heart condition you are born with. The word congenital means “present at birth.” Congenital heart disease can range from very minor conditions which never cause problems, to more serious conditions that require treatment.

A congenital heart defect happens when the chambers, walls or valves of your heart – or the blood vessels near the heart – don’t develop normally before birth. There are many different types of defects listed below.

1. Holes in the heart (septal defects)

When a baby is born with an abnormal opening in the wall that separates the right and left chambers of the heart (the septum), blood can leak between the chambers instead of flowing normally to the rest of the body. This may cause the heart to become enlarged.

The most common holes in the heart are:

Patent foramen ovale (PFO) is one type of atrial septal defect. The hole between the left and right atria usually closes within the first few years of life. Even if it doesn’t close, the hole may not cause any complications unless you have a second heart defect. PFOs are very common and many people will never know they have one.

2. Obstruction of blood flow

Stenosis is a narrowing or obstruction in heart valves, arteries or veins that affects the flow of blood. Atresia is when a passageway in the body is abnormally shut or has not formed properly. Different types of stenosis and atresia can partly or completely block blood flow in the heart.

Medication in the first few weeks of life can either close (or keep open) the ductus arteriosus. As your baby gets older and if the medication isn’t working, the ductus can be closed off using a cardiac catheterization procedure. This will restore normal circulation.

Other defects between the right and left sides of the heart often co-exist with transposition of the great arteries. An atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect or ductus arteriosus can actually help oxygenated blood circulate to the body.

Children with this condition often have an atrial septal defect as well (see above).